In In-depth

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

Just 2.1 per cent of medical research funding in the UK goes towards reproductive conditions, despite research which suggests that 31 per cent of women experience severe issues with their reproductive health, according to the 2020 UK Clinical Research Collaboration.

For a long time, and particularly since the publication of the Women’s Health Strategy in July 2022, it’s been well documented that such lack of research has led to slower diagnosis times and reduced treatment options for women. Despite this it was still news to many that, even when the little research into women’s health does occur, it’s not necessarily done in the most effective way.

So revealed the authors of new study Red blood cell capacity of modern menstrual products: considerations for assessing heavy menstrual bleeding. The report, published in the August 2023 issue of BMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health, is the first to compare absorption rates of menstrual products using actual human blood. Previously, individual manufacturers calculated the “collection capacity” of their products using liquids such as saline or water whose components are incomparable to menstrual blood.

In fact, the study revealed that since 1896 when Johnson & Johnson released the first “sanitary napkins for ladies” there have been “no industry standards” for capacity testing of menstrual products – except for tampons due to their historical link between absorbency and the risk of contracting the potentially life-threatening toxic shock syndrome (see boxout).

Whilst on the surface this may just seem like poor product testing standards, the report highlights the more worrying effects these findings could have on those who menstruate. Here’s what we know so far.

Data driven

The main objective of the study was to “measure absorbency and fillable capacity of a variety of commonly used menstrual products using human blood products”. This data will then be used to better allow clinicians to “quantify menstrual blood loss accurately”.

Some 21 products across the industry were observed, including menstrual cups, discs and tampons varying in absorbencies (regular to super plus) and sizes (0, 1 and 2). Pads from two manufacturers with varying absorbencies from pantyliner through to postpartum were also tested as well as period pants and perineal ice-activated cold packs.

Of all products tested, the menstrual discs were found to hold the most blood whilst period underwear held the least. Indeed, researchers stated that they found a “considerable variability” in the amount of human red blood cells that the different menstrual products could collect or absorb. Notably, it was discovered that there was a significant difference between the reported and actual capacity of many period products to hold or absorb blood. This, researchers say, is largely due to “product testing with non-blood liquids such as water or saline”.

The problem

But why does this pose an issue for women?

Well, principally due to the fact that the current validated clinical tool routinely used to assess menstrual blood loss, the Pictorial Blood Loss Assessment Chart (PBAC), is “highly dependent on traditional disposable menstrual products such as pads or tampons”.

Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) is thought to affect up to a third of menstruating individuals and is usually diagnosed when a woman is regularly losing more than 80ml of blood during one menstrual period (see boxout). Diagnosis of the condition is crucial as it could potentially lead to iron deficiency or signify other underlying diseases.

Managing menorrhagia

Heavy periods, known as menorrhagia, can be defined by the following symptoms:

- The need to change a pad or tampon every one to two hours or empty a menstrual cup more often than is recommended

- The need to use two types of sanitary product together, such as a pad and a tampon

- Have periods lasting more than seven days

- Pass blood clots larger than about 2.5cm (the size of a 10p coin)

- Bleed through clothes or bedding

- Avoiding daily activities such as exercise or taking time off work due to a period

- Feeling tired or short of breath frequently when on a period as this can indicate iron deficiency.

Heavy periods can be caused by a variety of things, ranging in severity. For example, many women will experience heavier menstrual bleeding when they first start their period, after pregnancy or as they go through the menopause. Outside of these milestones, however, menorrhagia can be an indication of certain conditions that affect the womb, ovaries such as polycystic ovary syndrome, fibroids, endometriosis, thyroid disease, pelvic inflammatory disease or – occasionally – womb cancer.

With this in mind, pharmacy teams should refer anyone who has:

- Heavy periods that affect their day-to-day life

- Heavy periods for extended amounts of time

- Severe pain during their period

- Bleeding between periods or after sex

- Other symptoms, such as pain when using the toilet or having intercourse.

As it is not always required, there is no set treatment as such for menorrhagia, however, pharmacy teams could advise customers that they may be offered prescription medications such as an IUS, the combined contraceptive pill, that which helps to reduce bleeding (e.g., tranexamic acid) or prescription-only anti-inflammatory painkillers (e.g., mefenamic acid).

Typically, using the PBAC, those who menstruate and need to change their pad or tampon every one to two hours are at risk of being diagnosed with HMB, but this may be too extreme. Indeed, the study found that “saturation of two heavy pads (100ml) or three heavy tampons (90ml) represents blood loss >80ml over the entire cycle”. This indicates that the current metric “greatly underestimates blood loss and rates of HMB” resulting in many women who suffer from HMB going undiagnosed.

Furthermore, in recent years, a wide range of alternative menstrual hygiene products have become available including menstrual cups, period pants or menstrual discs but the PBAC has not yet been modified to take these new products into consideration.

This step is key, researchers say, to identifying quickly and accurately when blood loss has reached “a critical level” and requires the patient to seek help. “The study found considerable variability in red blood cell volume capacity of menstrual products,” they add. “This emphasises the importance of asking individuals about the type of menstrual products they use and how they use them. Further understanding of capacity of newer menstrual products can help clinicians better quantify menstrual blood loss, identify individuals who may benefit from additional evaluation and monitor treatment.”

Tackling taboos

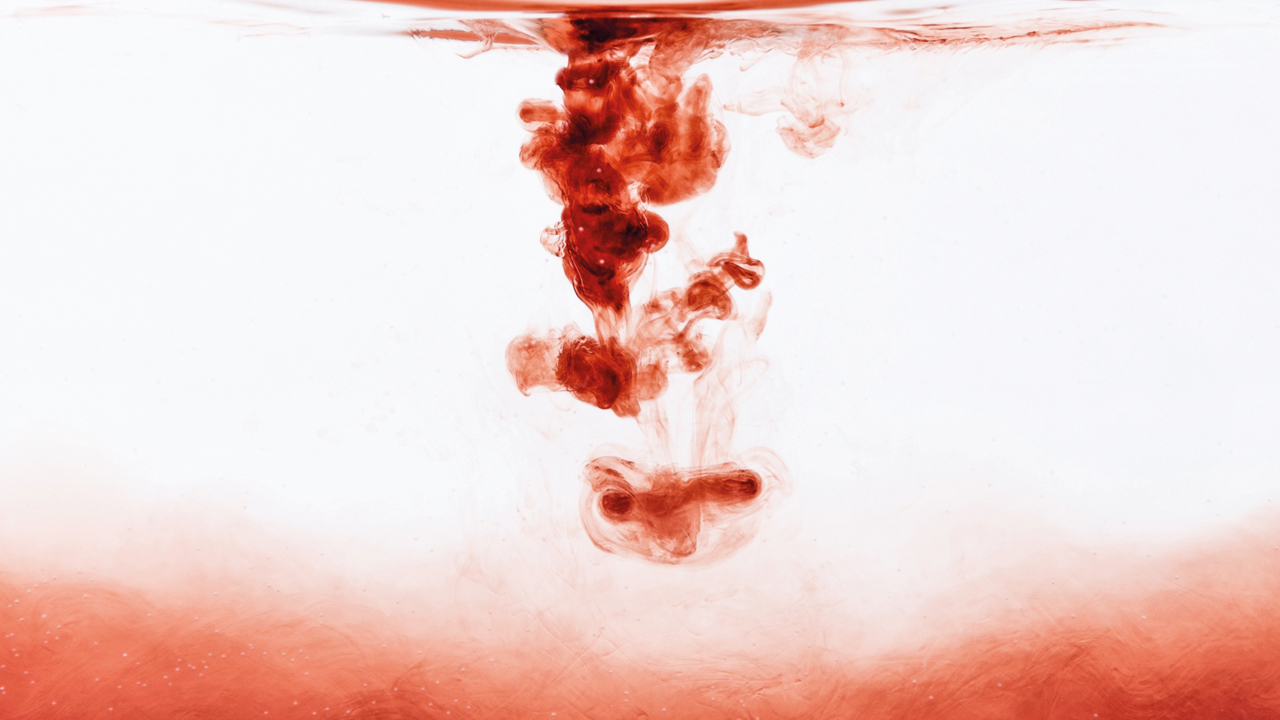

In a society where many still recoil at the word period, let alone the sight of menstrual blood, it is no surprise that HMB is a taboo topic in the wider public sphere. When this stretches to the medical world, this not only corroborates societal attitudes but is detrimental to the progress and better understanding of menstruation as a whole.

“Period blood in adverts has long been shrouded in secrecy and shame through the use of ‘blue blood’, said a spokesperson for UK-based period poverty charity, Bloody Good Period. “The fact that period product absorbency has only just started to be tested with actual blood shows just how far we have to go when it comes to menstrual health, bodily education and period normalisation.”

“A PubMed search of ‘menstrual blood’ resulted in one publication between 1941 and 1950 followed by a steady increase to a plateau of only 400 publications in the last several decades,” added Dr Paul D. Blumenthal, a professor of obstetrics and gynaecology at Stanford University. “During this time there were approximately 10,000 publications related to erectile dysfunction. The study modernises our understanding of menstrual product capacity by using red blood cells rather than saline. It provides practical, clinically relevant information to help patients match a product with their own menstrual protection needs and better plan for the expense.”

As patient-facing healthcare professionals, pharmacy staff can help to reduce such stigma within their communities by ensuring periods are an open topic of conversation in store. Charities such as the Bloody Good Period (bloodygoodperiod.com) or global youth organisation PERIOD (period.org) have a variety of resources on offer from posters to social media templates which teams can make use of.

Toxic shock syndrome

Toxic shock syndrome (TSS) is a rare but life-threatening condition caused by a bacterial infection. It is most common to get TSS from using tampons, menstrual cups, contraceptive diaphragms or caps, after a vaginal birth or caesarean section or from a cut or wound that has become infected. Chances of getting the infection increase if an individual has had it before.

Symptoms come on quickly and can include:

- A high temperature

- Muscle aches

- A raised skin rash that feels like sandpaper

- Flu-like symptoms.

If an individual suspects that they are suffering from TSS, they will need urgent hospital treatment, which can include:

- Antibiotics

- Fluids

- Medicine to control blood pressure

- Oxygen

- Surgery to remove infection from cuts or wounds.

Although TSS is rare, there are things that can be done to reduce an individual’s chance of catching or spreading the infection. Pharmacy teams should advise all those purchasing tampons, menstrual cups, contraceptive caps and diaphragms that they should always wash their hands before and after use, follow all instructions and never leave them in longer than needed or recommended.